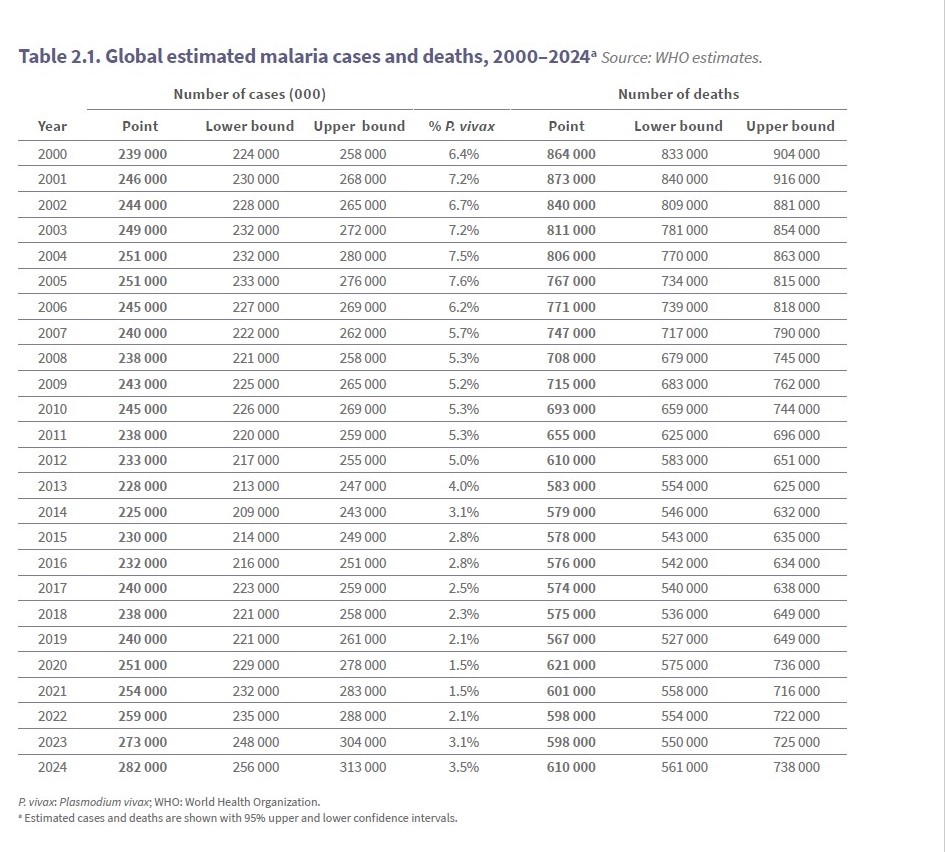

Malaria remains one of the world’s most persistent public health challenges, despite decades of global investment and technical progress. After years of decline, global malaria cases have risen every year since 2018. Cases increased from approximately 238 million in 2018 to an estimated 282 million in 2024. Mortality trends are equally concerning. The number of malaria-related deaths rose from an estimated 598,000 in 2023 to 610,000 in 2024.

The burden remains overwhelmingly concentrated in Africa. The continent continues to account for approximately 95% of global malaria cases and deaths. This signals renewed strain on prevention, diagnosis, and treatment systems [1].

Reports by the WHO and evidence from different case studies confirm that malaria is no longer a universal threat. As of July 2025, the World Health Organization (WHO) had certified 47 countries and one territory as malaria-free[2]. This demonstrates that elimination is achievable under certain conditions. However, this contrast raises critical questions:

- If elimination is possible, why have some countries succeeded?

- Why do high-burden countries continue to stagnate or, in some cases, experience resurgence?

More importantly, these disparities invite scrutiny of the global framework guiding malaria elimination. The WHO’s Global Technical Strategy for Malaria 2016–2030 sets an ambitious target. It aims to reduce malaria incidence and mortality by 90% by 2030. Yet progress has slowed, funding gaps persist, and emerging threats such as drug resistance and climate change complicate implementation. This prompts a necessary analytical question:

- Is the Global Technical Strategy structurally realistic under current political, economic, and funding conditions, particularly in high-burden settings?

- What differentiates sustained success from fragile gains?

This article investigates what is working in global malaria elimination efforts, what is failing, and why. By comparing successful elimination contexts with high-burden countries, it interrogates the role of financing. It also examines health system capacity, surveillance, innovation, and political commitment in shaping outcomes. Furthermore, it explores what must change for elimination to move from aspiration to sustained reality.

What Does Malaria Elimination Mean?

The global malaria community and the World Health Organization share a vision of a world entirely free from malaria. However, this goal can only be achieved through a progression of control, elimination, and ultimately eradication.

Malaria control refers to reducing malaria cases and deaths to manageable levels. While elimination is achieved at national or regional levels, eradication implies permanent global elimination [3].

“malaria elimination is defined as the interruption of local transmission of a specified malaria parasite species in a defined geographical area as a result of deliberate activities.”

-World Health Organization

In essence, countries that have eliminated indigenous transmission of malaria for 3 consecutive years request an official certification from the WHO.

The WHO global malaria strategy aims to accelerate the action among other countries to eliminate malaria. It urges endemic countries to work towards reducing the transmission of malaria. This goal can be achieved by following the new recommendations for the final phase of elimination. And these recommendations are divided into 3 categories of possible interventions: “mass” strategies, “targeted” strategies, and “reactive” strategies. All in a bid to tackle malaria at different levels[4].

Global Success And Strategies For Malaria Elimination

A. Countries That Achieved Elimination

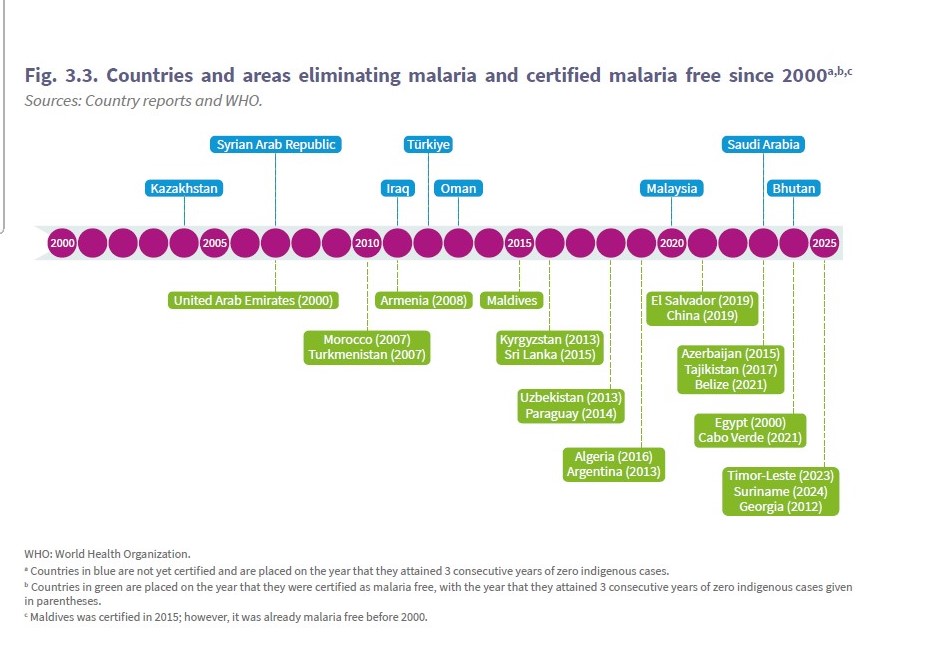

Eliminating malaria completely is not just a mere dream, but one that can be possible in Africa and beyond. Since 2017, the WHO Director-General has certified 14 countries as malaria-free. These countries include Maldives (2015), Sri Lanka (2016), and Kyrgyzstan (2016). Others are Paraguay (2018), Uzbekistan (2018), Argentina (2019), and Algeria (2019). Additionally, China (2021), El Salvador (2021), Azerbaijan (2023), and Tajikistan (2023) have been certified. More recently, Belize (2023), Cabo Verde (2024), and Egypt (2024) achieved this status. Georgia (2025), Suriname (2025), and Timor-Leste (2025) have also been recognized [5].

According to the Global Technical Strategy for malaria 2016-2030, countries, subnational areas, and communities are at different stages of the malaria eradication process. Regardless of whether it’s a high or low burden country, their rate of advancement will vary. It depends on the amount of investment made. It also depends on biological determinants, which pertain to the afflicted populations, parasites, and vectors. Environmental factors and the effectiveness of health systems play a role. Additionally, social, demographic, political, and economic realities[6] affect the progress.

With a severe shortage of health workers and doctors in Timor-Leste, the country was able to eliminate malaria from 223000 cases to zero from 2021 onward. They achieved this by investing and developing a three-tier health system. This system comprises national hospitals, reference hospitals, community health centres (CHCs), and health posts. It ensures most residents can access care within an hour’s walk. Currently, countries that have a sheer shortage of health workers can adopt this method to make significant progress in the elimination of malaria.[7]

B. Proven Tools and Approaches

Insecticide-Treated Nets and Vector Control.

Recent research highlighted that key interventions such as insecticide-treated nets (ITNs), indoor residual spraying (IRS), and larviciding significantly reduce malaria prevalence. They also reduce incidence across various countries. [8]

Between 2000 and 2015, there was a 70% decrease in malaria cases in Africa. Though there has been a serious concern to Insecticide Treated Nets (ITNs) usage due to the resistance to pyrethroids, and the insecticide used on all prequalified nets.[9] In countries like the DRC, significant insecticide resistance has hindered the effectiveness of traditional nets. This has led some to question their long-term role in eradication. Unlike other countries like Nigeria, Tanzania, and Ghana which showed a relative improvement in eradicating malaria using ITNs.[8]

An African family sleeping Insecticide Treated Nets.

Image: AI generated

The WHO also made an initial recommendation in 2017 to add the synergist piperonyl butoxide (PBO) to standard pyrethroid ITNs . This was followed by a strong WHO recommendation in 2023 for two new classes of dual active ingredient ITNs. Each class features a different mode of action. Pyrethroid–chlorfenapyr nets combine a pyrethroid and a pyrrole insecticide to enhance the killing effect of the net. Pyrethroid–pyriproxyfen nets combine a pyrethroid with an insect growth regulator that disrupts mosquito growth and reproduction. As a dual active ITN has been shown to be more effective than the normal pyrethroid-only ITNs in areas where mosquitoes are resistant to pyrethroids[9].

A similar case scenario can be seen in the global decline of the use of IRS in eliminating malaria. Between 2023 and 2024, there was a significant decrease in the number of people protected in India, Zambia and Mozambique [9]. A huge factor in this was a limitation as a result of operational and financial constraints. Yet, targeting the IRS on specific high-risk areas is more cost-effective in the long run[9].

Also, other innovative approaches enhance the effectiveness of malaria control efforts. These include the use of natural repellents, community-based adaptive strategies, and improved data management systems[8].

The Malaria Vaccine Implementation Programme (MVIP).

The World Health Organization has recommended using malaria vaccines to prevent Plasmodium falciparum malaria. This recommendation is for children living in highly endemic areas. The two malaria vaccines recommended for use include: RTS,S and R21/Matrix-M (R21).

In 2019, the RTS,S malaria vaccine was first introduced in selected areas like Ghana, Kenya, and Malawi. The results showed a 13% reduction in all-cause mortality (excluding injury). There was also a 22% reduction in hospitalization for severe malaria among children age-eligible for vaccination.

There was a priority given to subnational areas with the greatest need. This was in line with the principles outlined in the Framework for the allocation of limited malaria vaccine supply. As a result, initial global supply was difficult since early implementation was limited.

Toddler getting a vaccination by a pediatrician.

Image credit: AI generated

There was a later expansion in 2024 in the implementation of malaria vaccine beyond the MVIP countries. And so far, the vaccine has reached nearly 2.1 million children[9]. It is equally important that vaccines are complementary, not transformative alone, and cannot replace vector control or treatment access.

Improved Diagnosis and Treatment

Many countries have made great progress in reducing the incidence of malaria. They achieve this by early diagnosis through the use of a rapid diagnostic test and employing artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs). This has significantly reduced the death rates and limited transmission within the communities. The World Health Organization directly reported that Timor-Leste’s success in eliminating malaria was part of the country’s effort. They introduced rapid diagnostic tests and artemisinin-based combination therapy as part of the National Malaria Treatment Guidelines. Additionally, they began distributing free long-lasting insecticide-treated nets to communities most at risk[7].

Targeted Surveillance and Data-Driven Strategies.

The World Health Organization defines malaria surveillance as the “continuous and systematic collection, analysis and interpretation of malaria-related data.” This includes the use of that data in the planning, implementation and evaluation of public health practice.[10] However, the performance of surveillance systems varies markedly by context.

Countries such as China developed highly structured systems, including the WHO-endorsed 1-3-7 approach, which mandates reporting within 1 day, case investigation within 3 days, and response within 7 days, supported by strong digital platforms and cross-sectoral coordination, which contributed to elimination success and sustained detection of imported cases[11].

Thailand has adapted this model, establishing a near-real-time malaria information system (Malaria Online) that aggregates case data and enforces strict timelines, helping to accelerate progress toward elimination. Likewise, countries in the Greater Mekong Subregion, such as Cambodia and Lao PDR, have integrated similar surveillance strategies tailored to local conditions [12]. In the Americas, integrated platforms like Honduras’s SIIS (based on DHIS2) now support comprehensive malaria data capture nationwide, contributing to significant reductions in cases [13].

In contrast, many high-burden African settings struggle to achieve comparable surveillance performance. Persistent data quality gaps create challenges. Incomplete case reporting, especially from private and community sectors, adds to the issue. Digital inequities limit real-time reporting. Furthermore, governance constraints can delay outbreak identification and response. These factors highlight why surveillance approaches that succeed in low-transmission or digitally enabled settings may underperform in high-burden contexts. They need sustained investments in infrastructure, workforce capacity, and political commitment.

Multisectoral and Global Partnerships

A significant driver of global malaria elimination progress has come from multi-sectoral partnerships. Major financing mechanisms like the Global Fund to Fight HIV/AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria are especially influential. The Global Fund (GF) raises money in three-year cycles known as Replenishments. It pools public, private, and philanthropic contributions. These contributions are invested strategically in HIV, TB, and malaria and also help strengthen health systems. During its Eighth Replenishment period (2026–2028), launched in 2025, GF aims to secure USD 18 billion. This funding is necessary to accelerate progress against these diseases and to build more resilient health systems [14].

The Global Fund is now the single largest international financier of malaria programmes. It provides approximately 59% of all international malaria financing and has invested over US $20.3 billion in malaria control as of June 2025[15]. This funding supports key interventions, including insecticide-treated net distribution and case management, seasonal chemo prevention, and testing. As a result, there have been dramatic increases in coverage in regions such as sub-Saharan Africa.

Image source: Screenshot from GF’s Results Report 2025

In countries supported by the Global Fund, investments have greatly impacted malaria mortality rates. These rates have been reduced by more than 50% since 2002. This progress occurred even as the population continued to grow. Without these investments, modelling suggests that malaria deaths and cases would have been far higher [16].

For the 2023–2025 funding cycle, about US $4.18 billion (≈32 %) of Global Fund allocations to African countries was set aside for malaria. This underlines the disease’s priority within the portfolio [17].

The Global Fund’s investments work alongside governments, regional partners, and civil society organizations. These investments illustrate the impact of strategic financing from global partnerships. This financing has materially shaped malaria elimination strategies. However, sustained and increased commitments are critical if progress is to be maintained and expanded.

What Is Not Working Towards Malaria Elimination?

Despite important achievements in malaria control, progress toward elimination has stalled. In some places, it has even reversed. This is due to several interacting factors that extend beyond simple descriptions of challenges.

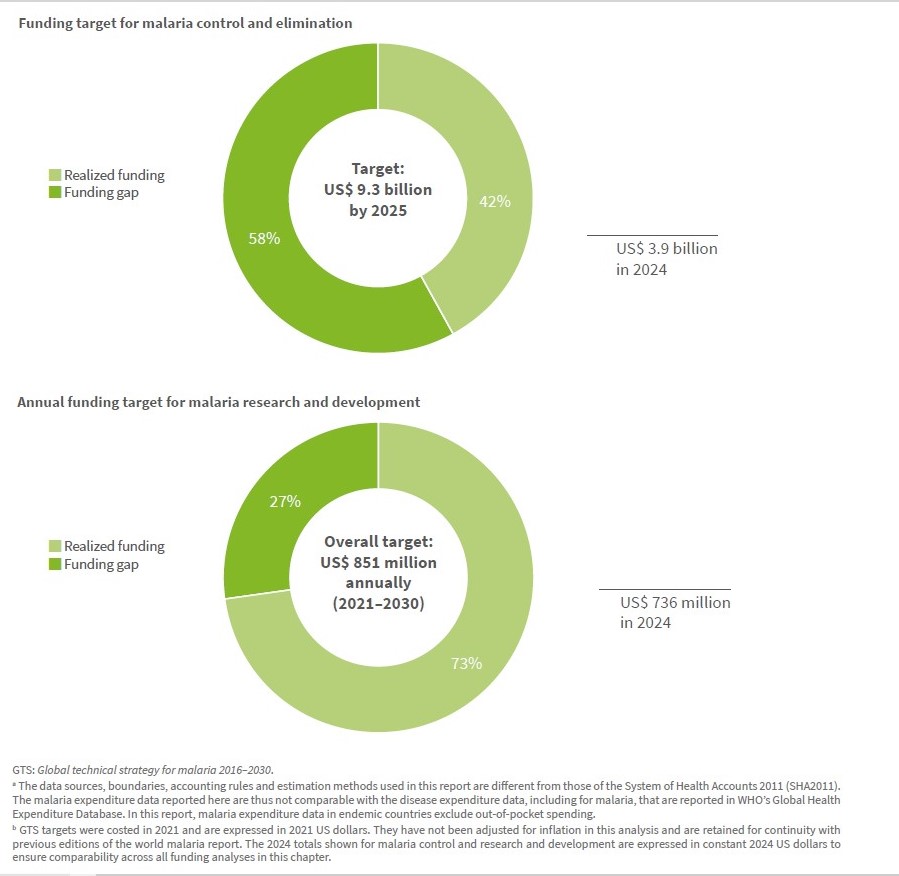

Funding shortfalls

In 2024, global investments in malaria programmes reached only US$3.9 billion. This amount represents barely 42% of the US$9.3 billion target set under the WHO Global Technical Strategy for Malaria 2016–2030, leaving a projected funding gap of about US$5.4 billion. The resulting shortfall has forced many endemic countries to postpone or scale back essential interventions such as ITN distributions and seasonal malaria chemo prevention campaigns. It has also reduced the capacity for routine surveillance and malaria surveys. These disruptions undermine the ability of health systems to maintain momentum, making them vulnerable to resurging transmission rather than resilient elimination efforts [9].

The reliance on donor funding creates additional fragility. In countries highly dependent on external aid, abrupt reductions in Overseas Development Assistance (ODA) have already led to cancelled campaigns. They have caused stock-outs of rapid diagnostic tests and antimalarial drugs and derailed planned vector control activities precisely because domestic financing has not been sufficient to absorb these losses [18].

In Zimbabwe, for example, sudden cuts in U.S. health aid severely disrupted entomological research support and community distribution of mosquito nets. These disruptions contributed to an over 180% spike in malaria cases and a more than 200% increase in deaths in just months of funding withdrawal[19].

Resistance to antimalarial drugs and insecticides

“New tools for prevention of malaria are giving us new hope, but we still face significant challenges,” said Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, WHO Director-General. “Increasing numbers of cases and deaths, the growing threat of drug resistance and the impact of funding cuts all threaten to roll back the progress we have made over the past two decades. However, none of these challenges is insurmountable. With the leadership of the most-affected countries and targeted investment, the vision of a malaria-free world remains achievable.”

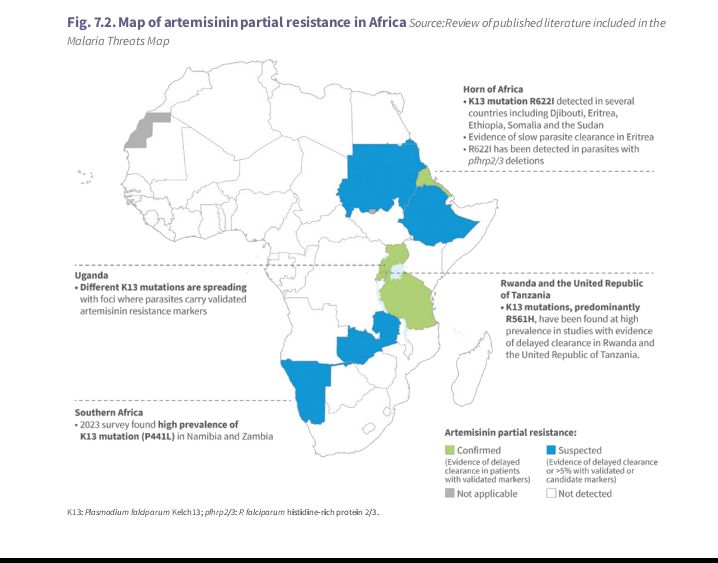

A screenshot from the WHO World Malaria Report 2025, highlighting an Africa map with countries with partial resistance to artemisinin derivatives.

The WHO’s latest report confirms that partial resistance to artemisinin derivatives, the backbone of first-line treatment, has been confirmed or suspected in at least eight African countries. These countries include Eritrea, Rwanda, Tanzania, Uganda, Ethiopia, Namibia, Sudan and Zambia. There are early signs that some partner drugs may also be losing efficacy. This multidrug resistance threatens treatment effectiveness. It requires more frequent updates to treatment policies and accelerated drug development. Yet, funding and regulatory pathways for new antimalarials remain slow and under-resourced. At the same time, widespread pyrethroid resistance in mosquito vectors undermines the impact of standard insecticide-treated nets. This resistance necessitates more expensive dual-ingredient nets that many programmes struggle to finance and deploy [9][19].

Health system weaknesses in high-burden settings

Weak surveillance systems and chronic shortages of trained health workers are significant issues. Limited laboratory capacity and fractured supply chains also contribute to the problem. As a result, many infections go undiagnosed, untreated, or unreported, perpetuating transmission cycles. These systemic gaps often compete with other urgent health priorities for resources and attention, fragmenting efforts instead of integrating them into robust primary care platforms[20].

Climate change

Shifting temperature and rainfall patterns are extending mosquito breeding seasons and expanding transmission into new ecological zones, including highland areas and urban fringes previously considered low-risk. Extreme weather events, floods, droughts and heat waves further disrupt health services and increase outbreak risks, especially in communities already vulnerable due to poverty, migration, or displacement.

Together, these factors reveal that stalled elimination reflects not a lack of tools, but structural fragility across financing, innovation, health systems, and environmental resilience.

What Must Change To Accelerate Malaria Elimination

Understanding what must change to accelerate malaria elimination requires confronting both structural barriers and political–economic realities.

Increase domestic financing

Many endemic countries operate within constrained fiscal space. They face competing health priorities and generate limited tax revenues. This situation makes malaria funding a political choice rather than a technical inevitability. Although the WHO has consistently emphasized domestic financing as essential for sustainability, global malaria investments continue to fall well below agreed targets, deepening reliance on unpredictable external aid. Achieving long-term resilience will require incremental budget reallocations, legal commitments such as ring-fenced malaria budgets, and multi-year domestic financing frameworks capable of withstanding political transitions and economic shocks.

Image source: Screenshot from World Malaria Report 2025

Innovation

Innovation must be linked to policy and regulatory environments that can absorb and deploy new tools effectively. There is promise in next-generation antimalarials. Vaccines, diagnostics, and digital surveillance platforms also show potential. However, the pipeline is constrained by slow regulatory approval processes, under-funded research and development (R&D), and limited incentives for pharmaceutical investment in diseases of poverty. Addressing resistance and stagnation in innovation requires collaborative governance mechanisms. These include advanced market commitments, pooled procurement agreements, and accelerated regulatory pathways. These strategies align commercial incentives with public health goals.

Strengthening community Health systems

Community health workers and local leaders remain central to case detection, treatment adherence, and vector control, yet they are often underpaid, poorly supported, and excluded from decision-making. Genuine community empowerment requires clear accountability mechanisms. These include performance feedback tools, for example, the ALMA Scorecard, which tracks malaria progress across African countries. Additionally, transparent reporting holds national programmes and donors accountable for service delivery and resource flows. Civil society organisations and district health councils can further act as watchdogs to ensure interventions reach intended populations and that data informs action.

Achieving malaria elimination will require political leadership willing to make difficult budget choices and transparent multi-stakeholder governance structures. Accountability frameworks are essential to ensure commitments translate into measurable outcomes at community and facility levels.

The global malaria agenda can transition from aspiration to sustained progress. However, it requires aligning political incentives, financing systems, and implementation capacity.

Conclusion

Global evidence shows that malaria elimination is achievable. The experiences of countries that have successfully eliminated malaria demonstrate that sustained progress is possible when long-term investments, strong health systems, and context-specific strategies are consistently applied. Meanwhile, these success stories should not obscure the reality that elimination has been uneven, fragile, and often difficult to sustain in high-burden settings.

Many countries continue to struggle with persistent transmission, constrained resources, and systemic barriers that slow progress. Achieving the global target of a 90 % reduction in malaria incidence and mortality by 2030 will therefore require more than technical tools or renewed optimism. It will demand deliberate action to address structural weaknesses in financing, health systems, surveillance, innovation pipelines, and political accountability.

Malaria elimination is not inevitable. It remains possible only if global and national actors commit to equity-driven financing, strengthen domestic health systems, invest in innovation that keeps pace with resistance and climate change, and ensure that communities remain central to implementation and accountability. Without these conditions, gains risk stagnation or reversal. With them, elimination can move from aspiration to durable reality.

References

- World Health Organization, Global Malaria Programme. World malaria report 2025 [online]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2025 [Accessed 14 January 2026]. Available from: https://www.who.int/teams/global-malaria-programme/reports/world-malaria-report-2025

- World Health Organization. WHO calls for revitalized efforts to end malaria [online]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 24 April 2025 [Accessed 14 January 2026]. Available from:https://www.who.int/news/item/24-04-2025-who-calls-for-revitalized-efforts-to-end-malaria

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Strategies for reducing malaria’s global impact [online]. Atlanta (GA): CDC; 1 April 2024 [Accessed 14 January 2026]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/malaria/php/public-health-strategy/index.html

- World Health Organization. Recommendations on malaria elimination [online]. Geneva: World Health Organization; [date unknown] [Accessed 14 January 2026]. Available from:https://www.who.int/teams/global-malaria-programme/elimination/recommendations-on-malaria-elimination

- World Health Organization. Countries and territories certified malaria‑free by WHO [online]. Geneva: World Health Organization; [date unknown] [Accessed 14 January 2026]. Available from:https://www.who.int/teams/global-malaria-programme/elimination/countries-and-territories-certified-malaria-free-by-who

- World Health Organization, Global Malaria Programme. Global technical strategy for malaria 2016–2030 [PDF]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015 [Accessed 14 January 2026]. Available from: https://acrobat.adobe.com/id/urn:aaid:sc:EU:ae3d2875-0668-41b4-b3fc-9e97177bf770 ISBN: 978 92 4 156499 1

- World Health Organization. Timor‑Leste certified malaria‑free by WHO. [online]. WHO: Geneva; 2025 [Accessed 14 Jan 2026]. Available from:https://www.who.int/news/item/24-07-2025-timor-leste-certified-malaria-free-by-who?

- African Field Epidemiology Network (AFENET) Journal. Effectiveness of malaria control interventions in resource limited countries: a systematic review [online]. [Location unknown]: AFENET Journal; 2025 [Accessed 14 January 2026]. Available from:https://afenet-journal.org/effectiveness-of-malaria-control-interventions-in-resource-limited-countries-a-systematic-review/

- World Health Organization,World malaria report 2025: Addressing the threat of antimalarial drug resistance [PDF].Geneva: World Health Organization; 2025[Accessed 14 January 2026]. Available from:https://acrobat.adobe.com/id/urn:aaid:sc:EU:1d07253c-d7a6-4c6b-a03d-9dc85008fe4d

- World Health Organization.Global Malaria Programme, Surveillance [Online].Geneva: World Health Organization; [ no specific date) [Accessed 14 January 2026]. Available from:https://www.who.int/teams/global-malaria-programme/surveillance

- Yi, B., Zhang, L., Yin, J. et al. 1-3-7 surveillance and response approach in malaria elimination: China’s practice and global adaptions. Malar J 22, 152 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-023-04580-9

- Lertpiriyasuwat, C., Sudathip, P., Kitchakarn, S. et al. Implementation and success factors from Thailand’s 1-3-7 surveillance strategy for malaria elimination. Malar J 20, 201 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-021-03740-z

- Mogojwe H. Stronger surveillance systems propelling Mesoamerican countries to malaria elimination – Clinton Health Access Initiative [Internet]. Clinton Health Access Initiative. 2021. Available from: https://www.clintonhealthaccess.org/blog/stronger-surveillance-systems-propelling-mesoamerican-countries-to-malaria-elimination/

- Replenishment [Internet]. Theglobalfund.org. 2023 [cited 2026 Jan 14]. Available from: https://www.theglobalfund.org/en/replenishment/

- Malaria [Internet]. Theglobalfund.org. 2024. Available from: https://www.theglobalfund.org/en/malaria/

- Results Report 2024 [Internet]. Theglobalfund.org. 2024. Available from: https://www.theglobalfund.org/en/Results/?utm_source

- Bureau T. Analysis of Global Fund Allocation Letters 2023-2025 Cycle [Internet]. African Constituency Bureau. 2023 [Accessed 14 January 2026 ]. Available from: https://www.africanconstituency.org/analysis/analysis-of-global-fund-allocation-letters-2023-2025-cycle/

- World Health Organization.New tools saved a million lives from malaria last year but progress under threat as drug resistance rises.[online] Geneva: World Health Organization; 2025 [Accessed 14 January 2026]. Available from:https://www.who.int/news/item/04-12-2025-new-tools-saved-a-million-lives-from-malaria-last-year-but-progress-under-threat-as-drug-resistance-rises

- Guardian staff reporter. Malaria “back with a vengeance” in Zimbabwe as number of deaths from the disease triple [Internet]. the Guardian. The Guardian; 2025. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2025/jul/19/health-malaria-mosquito-deaths-zimbabwe-trump-usaid-cuts-disease-control

- World Health Organization, Malaria progress in jeopardy amid foreign aid cuts. 2025 [online]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2025 [Accessed 14 January 2026]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/11-04-2025-malaria-progress-in-jeopardy-amid-foreign-aid-cuts

Leave a comment